xcelsior izmanto sīkdatnes (“cookies”), lai veidotu šo mājas lapu ērtāku jūsu lietošanai. Sīkdatnes ir anonīmi dati, kas nesatur privāto informāciju. Uzzināt vairāk

✕| 21. October, 2020 |

| All posts |

| Previous post: Vitra Summit 2020 apskats: jaunais normālais |

| Next post: Kas sekos "mašīnai dzīvošanai"? |

Work from home

The way offices and teams function recently has experienced radical changes.Well-known design critic Alice Rawsthorn looks back at the history of the home office and risks a glance into the future.

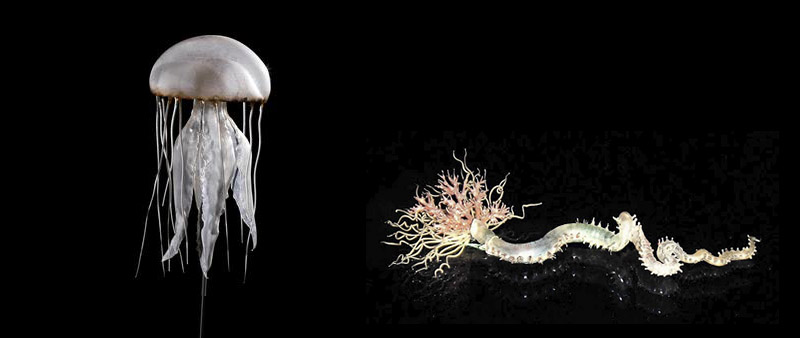

Having established a thriving business by designing and making glass replicas of sea creatures and plants during the late 1800s, Leopold Blaschka bought a big house in Dresden and kitted it out as a workshop and research laboratory. In pride of place was an aquarium where he and his son Rudolf could study live jellyfish, sea slugs, snails and octopuses before dissecting them. Working alone, without assistants, the Blaschkas sold thousands of their eerily accurate glass replicas to natural history museums all over the world.

After Leopold’s death in 1895, Rudolf continued their work on his own, spending almost all of his time in the workshop. No one was allowed to enter without his permission, which was rarely given. Rudolf even refused to come out for meals, which were delivered through a specially installed hatch in the door.

If only all home workers were as efficiently equipped as the Blaschkas! Most of the millions of people who have set up impromptu workplaces in their homes during the Covid-19 pandemic are likelier to be battling against dodgy Zoom connections, ailing smartphones and implacable kids demanding their attention than to be calmly contemplating a bespoke research resource like a lovingly stocked aquarium.

Historically, home working was a demographically polarised activity that tended to be restricted to the very rich and the desperately poor. People either toiled in their homes on pitifully paid piecework, such as sewing dresses or laundering shirt collars, or worked at home by choice because they were rich and powerful enough to call the shots. This process was rife with gender bias as the impecunious piece workers were often female, and the wealthy plutocrats mostly male.

Even a woman as accomplished and well connected as the novelist Virginia Woolf concluded in 1928: «A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.» Woolf was painfully aware that very few of her sex had the faintest hope of having either.

From the Industrial Revolution until fairly recently, most people worked outside our homes in factories, offices, public buildings or outdoors. Those places and our ways of working in them were designed accordingly.

In his 2011 book, A Taxonomy of Office Chairs, the US industrial designer Jonathan Olivares describes how early office furniture was mostly customised, often by its user, like the pioneering wheeled desk chair devised by the British naturalist Charles Darwin in the 1840s.

An avid tinkerer, Darwin replaced the legs of a wooden armchair with cast iron bed legs mounted on castors so he could roll himself around his study to scrutinise the rows of specimens laid out on long tables by his assistants in his home in the Kent countryside.

Olivares also describes how twentieth-century workplace design reflected broader changes in corporate culture by becoming increasingly standardised and hierarchical. The French film maker Jacques Tati satirised this brilliantly in 1967’s «PlayTime» by depicting his bumbling anti-hero Monsieur Hulot trying – and failing – to navigate row upon row of seemingly indistinguishable cubicles in a dystopian modern office.

By the turn of this century, the availability of affordable communications technologies enabled more of us to choose where we worked. The French brothers, Ronan and Erwan Bouroullec started out by designing flexible furniture that could be reconfigured to meet the changing needs of their Generation Rent contemporaries, many of whom lived and worked in the same places, often in cramped open-plan spaces shared with others.

In 2002’s Joyn, their first project for Vitra, the Bouroullecs applied the same principles to external workplaces by developing a modular desk system with adjustable screens that could create private areas for individuals as well as being opened up to accommodate meetings. Two years later, they introduced the Joyn Hut, a mobile enclosed workspace that could be moved around, often to create small temporary offices within bigger ones.

The same principles have dominated the design of our work environments ever since, not least as soaring commercial rents have prompted businesses to economise on space by encouraging employees to work from home. So far, most home workers have adopted the improvisational approach to workplace design favoured by the Blaschkas and Darwin, although few have been as bold as the Spanish furniture designer Fernando Abellanas, who, unable to afford studio rents in Valencia, constructed a suspended workspace with a desk, seat and shelves beneath a concrete road bridge.

What will be the impact of the sudden surge of compulsory home working during Covid-19? The expectation is that lots of people will choose to continue after the pandemic. «Working from home works – but will anyone want to go back to the office?» ran a recent headline in «The Guardian». And why would they? Long-term devotees of home working (like me) often sing its praises. The ability to focus on your work devoid of distractions. The freedom to chop and change your schedule as you please. Rustling up delicious snacks. Avoiding arduous commutes and tedious office politics. Sneakily watching an episode of vintage «Top Boy» in the middle of the afternoon. And so on.

But most of us have chosen to work from home and have been able to kit out offices, studies or desks to meet our needs. There is a huge difference between choosing to adopt a new way of working and suddenly being forced to do so. Not every «ingénue» home worker will emerge from the pandemic having written that novel, completed a long-planned research project or learnt a new skill.

For some, it will be remembered as a time of anguish over failing relationships, financial crises, or losing loved ones to Covid-19. Even for those who are spared such distress, the collective trauma may prompt them to radically reconsider how they wish to live and work in the future.

Some people will crave the security associated with conventional choices, such as regular employment in a formal workplace. Another group could be drawn to seemingly riskier options that offer greater independence and personal freedom, possibly because they feel empowered by the strength and resilience that they themselves displayed or observed in others during the crisis.

Others will be compelled to continue to work remotely by financially strapped employers who are desperate to cut costs. Those employers will then face the challenge of designing digital ways of nurturing the camaraderie, shared sense of purpose, water-cooler opportunities to spark new ideas in chance conversations and other advantages of traditional shared work places among their dispersed staff.

Whatever the outcome of the Covid-19 crisis, and whenever it ends, our ways of working, like so many other aspects of our lives, will never be the same.